What Dancers Know ...

"Subject Knowledge" is the most important camera skill.

Roxanne Kamayani Gupta - 1974 - Bharatanatyam in Seneca Falls, New York.

Roxanne had returned to upstate NY after studying in Hyderbad, Southern India.

These were my first pictures of a dancer.

I knew nothing about dance and was totally in the dark about which frames were good and which frames were not good.

Thank goodness Roxanne was picking and directing shots but I have to admit, I was still in the dark until years later.

Her Book:

"A Yoga of Indian Classical Dance: The Yogini's Mirror" http://www.amazon.com/Yoga-Indian-Classical-Dance-Yoginis/dp/0892817658/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=booksPhotographers:

You can know composition, rule of thirds, exposure, darkroom, Photoshop, all the features of your camera, the menus, the color settings. You can have the most expensive DSLR and all the "envy" lenses available, shoot in RAW while holding down the shutter set to "C" for continuous and motor-drive at 7-frames-per-second and then make huge paper prints from 14-bit files. You can hang two or three cameras around your neck and grab first one then another. You can have press passes, and security badges and backstage passes. You can know the mayor, the butcher and drive a Mercedes. But without subject knowledge you don't know what to shoot, when to shoot or what to select from your take.

- Subject knowledge and any simple camera - the simpler the better - and you can outshoot anyone.

- Dancers already have subject knowledge of dance.

- Most photographers need to aquire that knowledge.

You don't even have to wait for the results to know what the photographer is shooting. Just listen. Motor drives and frantic clicking tell you the photographer is lost. I know the equipment is impressive looking but knowing what to shoot is most important.

Vanessa Gibbs' West African Dancing gets an audience member up to dance at City in Motion for a class recital.

Note: the exteme wide-angle distorts the dancer at left. She later left a note next to the picture on CIM's wall stating, "Objects in picture may be smaller than pictured. - ha!"Planting and Harvesting

Click for Larger Version

"Dear Friend" by Sabrina Madison-Canon - Dancer Katie Jenkins - Modern Night at the Folly Jan 2005 - Photo Mike StrongThere is a huge conceit in journalism in general, but even more so in photography. The conceit is unconcious, even madated by the rules of the occupation in terms of conflict of interest, so it continues unrecognized, but this conceit is roughly charecterized as, "I show up and take notes" or "I show up and start clicking with the camera and now I have an accurate picture of what occured. The camera captures all." These are not in large part arrogant or conceited people, at least I can't think of anyone I know that I would label that way and I can't think of anyone I don't really like or anyone who I would ever imagine intentionally doing a junky job. They just make certain assumptions about graphics over knowledge.

In other words, just clicking the shutter button and recording an image is assumed to be information gathering. This is the wrong approach. As a photographer, you need information before you start clicking. You need to think of shooting as harvesting data based on information you already have. I can't think of any journalist recommending doing an interview without first doing research on their subject. Yet that is what most photojournalists do most of the time. Perhaps because a picture by itself contains information, even though it may be information which mis-represents the subject.

When you, as photographer, click the shutter button you are not getting knowledge, you are harvesting information based on what you know about the subject. If you don't know much you won't get pictures with information except by chance. You have to know enough to be able to harvest (shoot and then choose) those moments which represent the dancer, the company, the piece and so forth.

Subject Knowledge and Time Spent

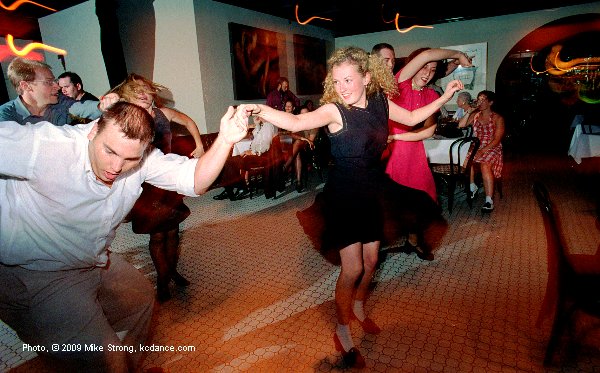

Swing at Raoul's Velvet Lounge (1998) Overland Patk 119th and Metcalf - to the music of Dave Stephens - Alan Akers (left) and Gretchen ...Photographer Pages

- Both Gjon Mili and Barbara Morgan laid the foundation for all of today's dance photography. Neither were dancers, at all.

- Gjon Mili was an engineer and self-trained photographer who introduced electronic flash to dance and sport

- Barbara Morgan - was an artist who became a photographer bringing dancers to her studio

- W. Eugene Smith - knowlege and art - Not a dance photographer but someone you should know about because he is local (regional: Wichita) and because he lived with his subjects, for months to years.

Dance is both social ornament and cultural glue

Dance Books at Borders - less than half of one shelf sectionThe only dance books you will find in the whole of the entire Borders Books in Overland Park is on the lower shelf of the middle section of shelves and only in the part of the shelf to the right of the black separator which sticks out from the shelf. Dance seems to be both omnipresent and neglected, requested and shoved aside, at the same time. This picture was taken August 2009 (They are out of business as of July 2011 when Borders went backrupt across the country.).

I've found myself perplexed over the years that dance should be both ubiquitous and discounted. Social/cultural events are certain to feature dance. Yet try posting a dance video to YouTube. There is no dance category or Vimeo or many others. You need to post as entertainment and add keywords for dance. This too seems to be nearly universal among places to post information and video. I thought it would be nice to add a Digg.Com feed to my KCDance site. I could get entertainment news bits but again, no category for dance and no way to get just dance.

Including the little ones as active participants in the community as performers in Fiesta Mexican, 25 Septiembre 2009, Guadalupe Center, Kansas City, MO - A 30th Anniversary concert and fundraiser for El Grupo Folklorico Atotonilco - here they are in Veracruz outfits.And yet dance is a place where people get together across many social lines and occupations. At fiestas, where the celebrations are like large family gatherings, everyone congregates around the dances and the crowd is filled with the parents of the youngest dancers. Dance brings otherwise disparate people together. We dance to go to war, to hunt, to marry, to say goodby, to express ourselves.

In the late 1990's and early 2000's, as www.kcdance.com, I tried many times to get dance people interviewed on KCUR talk shows, nothing came of it other than by chance. Everyone else seemed to get interviewed, but dancers, unless with KCB, seemed to get short shrift. Photographers from the paper who showed up at dance events seemed to be oblivious to the dance and seemed to be looking for something to fill their composition for their daily assignment. They were gone as soon as they showed up and I've never seen even one of them get out on the dance floor to dance. I used to have a suspicion that the news media avoided dance because they were afraid to get out and dance.

Shooting bands, singers and theater is easier anyway. Not much motion. You can move around the subject and shoot from just about anywhere looking for just the right angle. In the absence of knowledge, any subject is difficult to shoot well. When that subject just moves and moves and when you also don't have any idea what the moves are, the subject is even more difficult to shoot. Then again, you would have to learn who is connected to whom.

Subject Knowlege In General - Examples

Deficient subject knowledge is not limited to dancing or photography. I've seen the same thing happen in other areas. For example in a database job I had, my position was to have taken over from outside contract programmers who were finishing a large job of designing software for the business (selling heavy-equipment construction parts across the world).

Contract Programmers vs Home-Grown

The new web program had to allow large listings for wholesalers (rather than the simpler shopping cart software you are used to) and then it had to control the purchase, inventory, picking, packing, shipping process from multiple locations and a lot more. This company had already written its home-grown software which worked, but this special-build was supposed to be a pro job.

It was being done by what was then one of the largest such temp contract programmers in the US. But there were a couple of weaknesses in the pro job. While the home-grown package wasn't as fancy but it came from people who worked the job and who knew their own business from years of experience, hands on experience and muscle memory.

The big pro job had big bells and whistles but sent out web pages too large to be downloaded at the client end, which could be in Johannesburg, South Africa, or Mumbai, or Saudi Arabia. The company itself, located in KCs west bottoms, had the fastest broadband available but the customers were often on POTS (Plain Old Telephone System) and lucky if they could even run at 56kb. The hundreds of lines of product listings (no simple shopping carts) sent out megabytes of clunky HTML code which could not be handled by systems in other parts of the world. The new shiny software worked on the Dev Boxes (development boxes [computers]) in house but not in South Africa.

Eventually all that code had to be replaced, by home-grown programmers. These were people in the company who came from the ground up in the warehouse and the sales ends of the business and then learned to program. The people who actually worked in the warehouse knew their business better than anyone specializing as programmers who came from the outside and didn't know the business.

At least several hundred-thousand dollars and two or three years were spent trying to make the big pro job work. Eventually it had to be scrapped. The in-house people learned programming better than the programmers learned warehouse and sales. The hired pros should have spent time working in the warehouse and in the sales office before they started programming. It is equivalent to shooting pictures before you understand what you are shooting.

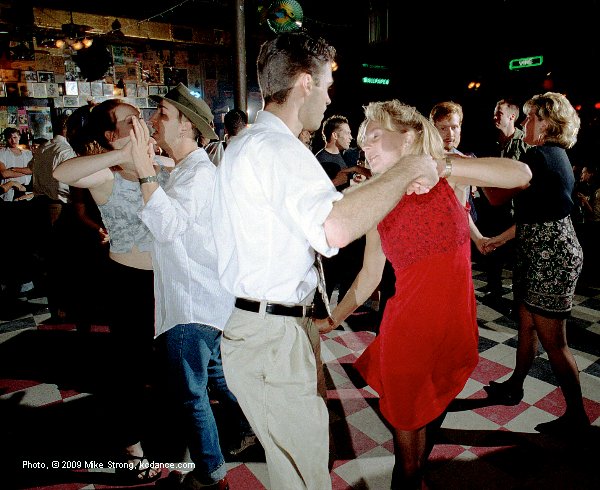

CD Release Party, August 30th 1998 at the Hurricane in Westport for Dave Stephens Swing Band. Dave Stephens far left on the microphone, Rod Fleeman on guitar, Milt Abel on upright bass - 20mm lens on Nikon flash on camera and remotely left and right. Bubbles from Dave's bubble machine.The Group Picture

Some years ago, at the start of the 1990s I was gallery director for the now-defunct Society for Contemporary Photographers in Kansas City. The gallery was in the Rivermarket and we had an exhibit of pictures of Appalachia. I was going through the display with a friend, Gwen, when she stopped and stared for a long time at one of them, one I hadn't been that impressed with. It was a nice enough picture but seemed ordinary to me.

It was a shot of a group of children sleeping together on the floor with one child, a girl, older than the rest, though still quite young, with her eye open, watching the camera. To me, just another shot of a group of kids. To Gwen, this picture was a stomach-stopping reminder of something she knew well. This, she explained, was the story of so many families. The parents had to go to work and whoever was oldest among the children would be responsible for watching the younger children until the parent returned, late that night.

Gwen had the most intimate kind of subject knowledge. I had simply passed over the image not understanding the meaning. I thought of this picture again when Judge Sonia Sota-Mayor was being criticized for her "wise Latina" comment. I knew how right her statement was about personal knowledge. It was similar to the way juries started out. Juries of our peers.

Juries of Peers

Today we are conditioned to thinking of jury pools in which any knowledge of the subjects, or the case or the people involved is considered grounds for disqualification. When I left massage therapy in November 1989 to finish up my four-year degree I drew a story about the jury system. One of my steady massage clients at the Kansas City Club had been Ralph Monaco, a lawyer and later a Missouri state senator. He had also been the lawyer re-enactor at Old Missouri Town where he would tell tourists and other visitors about law in 1855.

For my jury story Ralph told me that when the system began (centuries ago), jurors were required to know something about the case and the participants. That way they would not be swayed by attempts to guide a verdict by less than truthful questioning. For a modern reference instead of thinking "jury of your peers" you might think of the term "peer review."

A peer review is done with people who know the field and who can evalute some study, or method or theory, etcetera to see whether it stacks up against what they know. What if, like juries, reviews of specialized material were to be handled by people who know nothing about the speciality? Can you imagine having someone who knew nothing of medicine review a scientific article on a new heart medication trial? For that you need people who know the field. The field you know also shapes how you view the world.

Points of View

Anyone in a specialty sees the world at least partially through their own occupation. My Grandfather was a dentist for 58 and a half years and they always noticed people's mouths. "So and So has a closed bite," and so forth. We had a family friend who was a cabinet maker. He always checked out the cabinets in the house. My dad had a glass shop and put in store fronts. Even in retirement now, he always looks at the aluminum in window frames in buildings, restaurants and so forth, to see who manufactured the extrusions. Photographers look at framing, exposure and so forth but seldom look at the content because they usually don't have knowledge of their subject.

Tango workshop 1997 with Duo Lorca playing at Peregrine Hoenig's Fahrenheit Gallery (the first location), second floor in the west bottoms - Christine Bregs on violin and Beau Bledsoe on guitar. Fuji 400 film, 20mm on NikonGood Feet

A couple of pictures illustrate a lack of subject knowledge. These are pictures of a 2001 article about Terrence Poplar written by Paul Horsley.

Now in all fairness, I should note that it is my suspicion that this misunderstanding did not come from Paul, and not just because I like Paul Horsely. Paul is a keyboard guy who recognized the need to learn more about dance. He joined the dance critics association and took courses and workshops to learn. He really made the effort. In addition, he looked for local dance stories from the community in general and not only from the "big-name" companies.

This story bears signs that the photographer mis-understood the meaning of good feet in dance. She took the foot shot as if he is resting tired feet rather than with a dancer's meaning.

Photos, cutlines and headlines are sometimes suggested by the writer but more often the photographer figures out most shot ideas. The editor does most or all of the headlines. The editor also generally does the cutlines under the pictues with information from the photographer's notes.

But this is still a good example of outside experts not understanding what you do. The concept of "good feet" as understood by any dancer is so standard that most dancers don't realize that their usage, specific as it is to dance, is jargon. The framed article is just inside the door to the studio at KCFAA (Kansas City Friends of Alvin Ailey).

Here I've cropped out and pasted together the relevant section of the framed articlle (top picture)The relevant excerpts from the article:

1 - the quote from Winston in the text saying that Terrence "had nice feet." and

2 - the cutline under the picture (as well as the picture itself) is clearly a misunderstanding of the usage for "nice feet."I suspect that it was the photographer who was responsible for the cutline and the picture to go with it. That is indicated by looking at the overall pictures. They are all nice and rooted in standard rules of composition except the in-the-air dancing picture which is so-so at best. In other words she did several pictures which could just as easily have been office-worker pictures. And although they are nice they are not dance. The one picture showing Terrence in motion is markedly different in quality from the others. The positions of the dancers are awkward. Sometimes I think newspapers are thrilled they get anything in the air, regardless, good or awful.

My guess is that Paul understood the quote from Winston because he includes it within text about Terrence's abilities as a dancer, not about Terrence's physical health. Then, I am guessing, the photographer either overheard this at the timeof the interview and decided to picture Terrence's feet or just did feet anyway as a way of trying to show details.

Or she later, either read the article and found the shot to go with what she thought was the meaning of "nice feet" or the editor put "nice feet" together with the foot shot from the photographer. In either case we know the editor let this go through, so the editor seems not to have known the meaning either. From the look of the photos, probably the same for the photographer.

And that leads to a caution about sending out photos for publicity. Only send the one or two or so that you really do want to see published and which fit whatever they are illustrating. My experiences so far are that almost anytime you send the editors pictures to pick through, you assume that they will pick a good one for you, because they are photo editors. Instead pick the worst one. So make sure that you, the dancer, send a truly representative good shot or shots and no other shots.

It is a win, win. You look better and they look smarter.

David and Kendra, new dance floor, Dave Stephens Swing Band - Louis and Company 2001 - shutter speed about 1/15th second, flash on camera and remote behind the couple gives color and subject detail - Fuji 400 filmVisiting Photogs

When I first realized that news photographers simply didn't see dance as anything other than some motion in front of the camera to be caught as it came by (like swatting flies, me too, originally), I began to formulate tips and tricks I could convey to them about shooting dance. The thought was they would be able to use that information to improve their shots of dancers.

These are all good photographers and very competent. I haven't run across anyone I didn't like and think well of. I cannot imagine any of them ever wanting to turn out a poor job. Yet some of the very rules of journalism, as practiced today, almost mandate a no-knowledge job. Too much familiarity is viewed with some suspicion of being compromised.

Anyway, the newspaper shooters didn't seem that eager to learn about dance (but then I didn't have a workshop for them) and as I began formulating tips and tricks I might give them I realized there really were no tricks and tips. You had to do dance physically in order to see with your eyes. It is a physicalvisual/aural sensation.

When I took ballroom lessons I became aware of ballroom in ways I could not ever have understood from the "outside." In 1994 I had enough money as a programmer that I could afford the lessons and so I signed up. As a photographer since the summer of 1967 the camera just came with me. As I learned to dance, what I looked for in the viewfinder changed, almost by itself.

I need to make this point because most of you who are dancers have long forgotten or not noticed the wealth of information you carry around routinely. I still remember those transitional learning moments and so I can help to bridge the gap. Most of you started dance very early and you see and hear things in each dance and each rehearsal that a non-dancer is simply not aware of. So it is easy not to realize what an advantage it is to actually dance, even a little, when you are shooting dance, compared to photographing dancers purely from the outside.

I started dance much too late to expect to have the kind of awareness of all the small things going on in the dance that any working dancer knows both unconciously and conciously (implicit and explicit knowledge). My favorite contemporary dancer photographers, for the most part, are dancers or former dancers. I see something in their work which catches nuances of movement and position in ways that really show the dance and the dancer's experience. That kind of awareness makes even non-dancers excited by the images. And having said that I am now about to list mostly non-dancers.

Quick Note: Gjon Mili, who set the tone for most of what we see as dance photography today was an engineer and self-taught photographer. If he danced, I don't know it. But he did spend enormous time with dancers and musicians, even bringing them into his studio for jam sessions.

Likewise for Barbara Morgan who was an artist and only later a photographer. But Morgan consulted with the dancers and choreographers and spent sometimes weeks before bringing the dancers to her own studio to shoot 8-10 movements derived from the stage work. She worked directly with the dancers, literally looking into their eyes and reacting to changes in their pupil size as a trigger to shoot.

Lois Greenfield's influence is huge in dance photography yet she is not a dancer and has never been one. She did, and does, go to rehearsals and performances. As such, her main work perplexes me because she takes dancers into her studio where she separates dance from its own space and does "pure" photography in which dancers and their skills become raw ingredient bits and pieces submitted to her camera rather than dancing. I admit to studio envy, and, at the same time, to a love/hate relationship with her work. The first time I saw her work, it knocked me off my feet. Later, it seemed sterile.

I just revisited her site to look at her most recent images. I thought that perhaps I would warm more to her current work. Instead, it seemed divorced even further from how I see dance. [update: seems neat again, as design] It seems to take life and stop it - in a sort of photographic taxidermy, despite, or maybe because, of its beautifully and precisely engineered images. Still, visit her site. She is one of today's most successful photographers and probably one of the world's most sold. Greenfield has many copiers. Perhaps that alone has diluted the impact of her work for me.

[added thoughts] Greenfield is a superd stylist. Note her imitators (who look painfully imitative) and the amount of text here. Her work is often delightful. I don't have a disagreement with what she does, I just have a different focus. When you see her work you see Greenfield. I like to think that when you see my work you see the company or the piece rather than a Mike Strong photo. She reminds me of the late Francesco Scavullo, a superb stylist in portraiture. People went to him to get a Scavullo portrait rather then a personal portrait. All his work made everyone look more or less the same. Just different faces in the Scavullo style. He was world famous and very expensive. The pictures looked great but I don't think I ever got an inkling of who each person was, only what Scavullo had done with them.

Marty Sohl is a former dancer and a long time photographer of San Francisco Ballet and Lines Ballet. She has some of the most beautiful dance images which show an inner connection, and intimacy with dancers and dance which I really love. Sohl also has studio light but this is not standard photo-studio light. She clearly lights for an inner sense of the experience of dance. Compare this deeply personal work to Greenfield's.

The Effect of Personal Experience

After my first set of tap lessons I wanted to look at a documentary on Gene Kelly which I had watched just before those lessons. I wasn't trying to compare before and after, I just wanted to see it again. But my experience on viewing the video after a set of tap lessons immediately became a lesson for me in before and after.

Suddenly I heard Gene Kelly's taps in a way I could not hear it before the tap lessons. I realized that although I had heard him as he tapped before, in truth, I had not really heard him tapping. Not until I had "muscle memory" did I get it well enough to hear those taps and to hear how clean, delicate, consistent and strong his sound was. I really had not an inkling of how beautiful his work was until I had lessons.

I suppose that brings up the issue of what good is something if you need lessons to "get" it. Shouldn't the art be self-explaining? No. We are always more aware of what we ourselves participate in. If dance were aquired just by its presence then no dancer would need training. All dance would be purely spontaneous and there would be no gap in understanding between non-dancers and dancers. Also, all architecture would just somehow happen. Everyone would paint. We would all sculpt. And so forth. We do owe explanations to the audience and even to ourselves.

That brings us back to personal experience. With "muscle memory" I could take photos with an awareness of the architecture within "the moment." That is when I decided "If you don't hear it, you can't see it." I will never perform in a ballet, but I can get performance with my camera in ways I could not previously.

When the Jazz Museum first had exhibits I remember a museum item tag which noted that Duke Ellington didn't just hire musicians, he hired musicians who could dance. That, after all, is who he played for, people who came out to dance. Lots of swing dancers.

Grand Emporium on a swing night - Fall 1998 - 20mm on Nikon, Fuji 400 filmThat is the same experience I've watched again and again around Kansas City in dance floors. There are musicians who can play for dancers and musicians who are just not connected to dancers. To watch dancers in those circumstances is like looking at someone who just gets up a head of steam only to suddenly hit a brick wall when the music goes off into the personal space of the musician(s). Usually it is something jazzy. More than a few times I've heard dancers complain about musicians who go off on their own thing/style in the middle of a dance gig. You can watch them come to an abrupt stop, almost as if they had run into a door.

Chief Bey

Chief Bey, who learned African drums and played for Pearl Primus and Alvin Ailey talks about how Pearl Primus told him to always have the music there for her. Here is a quote from a PBS interview of Bey: (note: "bey" means "chief")

Chief BeySource URL: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/freetodance/about/interviews/bey2.html

This is from the middle of three pages. Be sure to read all the pages at PBS (use their previous and next links). What Chief Bey says is so compelling.Describe the drummer's relationship to dance in an African dance company.

Pearl Primus said a drummer should always pay attention to who is dancing in front of them. Pearl said, "Whenever a dancer is dancing in front of you, you must always keep your eye on the dancer. And you must never let the dancer fall or step into a hole. There must always be music. If she moves her foot, there must be a sound there. If she moves the elbow, a sound; her head, a sound. If she blinks her eye, you must try to make a sound for each one of these movements." ... "Because if the dancer steps into a hole, in reality she can really hurt herself, damage her limbs, come off the stage sore, and almost want to give up dancing." ... A drummer should never let a dancer step into a hole. And the hole is meant by no sound. And when she steps down on the floor, it must be on a sound. And when she raises up, it must be on a sound. It must never be a vacancy, see, so that that person is literally dancing on music.

I'm always looking at the feet. I'm always looking at the feet because the feet tells me what is happened, where they're going and where the accent is. Dance is such a language for the body that it's almost impossible to interpret. So you have to watch the dancer, because the speech that the body delivers is limited. So when you see the dancer moving, you try to help the dancer move in the direction that they're going. And doing so, you try to lift the dancer. You try to elevate the dancer so that the dancer is not really dancing on the floor, they're dancing on music and on the sound of music. I loved playing for moving bodies. Moving bodies inspire me to play. They also tell me that if you dance, you will never play something that they cannot dance to, huh? That's why all the drummers that I teach, I tell them, "You must learn to dance, because if you learn to dance, you will never play music that's outside for somebody else to dance to. You will always play dancing music because you know what dance is about if you dance. If you don't dance and you're only a drummer, you will play anything and expect them to dance. But if you are a dancer as well as a drummer, you will never play music that is outside for someone to dance on.

In a similar way, your camera has to be there as the dancer steps. Maybe we should try thinking about the shutter button like a drum. Step down is a click, Raise up is a click, always on the count.

Instead of counting:

1 and 2 and 3 and ....

Count:

click and click and click and ....

Or

1 click 2 click 3 click ....

and so forth.

Kansas City 2-Steppin' Contest finals in 17 Decmber 2005, Park Place Hotel - First Place Winners splitting $4,000 - Ron Thomas and Khadijah Robinson

http://www.kcdance.com/Dancing/TwoSteppinFinal_20051217.asp Nikon D200, 12mm lensAfter my first ballet lessons I became visually aware of details of body positions which before I had only experienced as some sort of motion with touch points. And although I've always been good at that, after each set of dance lessons I could see and feel a genuine jump in the quality of my dance shots. Tap was a major jump in listening. Flamenco took listening to a new edge because the dancer sets the beat and the musician follows so the responsibility for the count fell to me. Ballet delineated movement into awareness of individual small actions.

That is why I think there are no real hints or checklists you can make up which are usable in the moment if you don't already dance. You cannot conciously check off the points on a mental checklist in time to make shooting decisions. All the hints and tips really depend on "muscle memory" from dancing. This is also why I think any dancer interested in photography is perfect for this.

So, to re-cap. The closest thing to a tip for anyone is listen to the music and shoot on the beat. As advice goes, that is a bit mechanical but far better than the motor drive approach (watch my eyes roll and hear my heavy sigh). If shooting on the beat gets you enough results for further interest and if you are a photographer who doesn't dance, start taking dance lessons. As you take those lessons you will realize that the beat isn't just the beat. There is width to the beat and spaces within that width and dancers do different things at different locations within any beat (or off beat).

Think of a beat as a sine wave, or a trough, or a groove, a real space within time. The way a dancer comes into a beat, how long they are there and they way they exit, that tells you how to shoot. Part of your time in rehearsals is about getting this pattern both for the company and for each dancer, as they are at that time, or for that piece (maybe the center of gravity changes in a piece from what you've shot with them before, and so forth like the difference between Balanchine and Tudor). More shooting by itself won't add nuance. You need lessons plus shooting and you will keep adding nuance.

Shooting Tools, Continuous Drive and Panic/or/Catch-Up Shooting

Camera

You are the picture maker, not your camera and not some camera-designer engineers. Essentially you should be able to shoot good pictures with any type of camera, even a pinhole camera. In practice the camera you use will either hinder you (most cameras) or not get in your way. For almost everything in dance you want to shoot you will need a DSLR (Digital Single-Lens Reflex) type of camera, a lens with a wide aperture and fully manual control.

If you are shooting dance you will find that you are in a niche environment. Years of intense reading of camera reviews convinced me that no camera reviewer anywhere routinely shoots dance, nor, I am guessing, the combination of dim-light, high-motion conditions and the need to recognize good form and technique for both individuals and groups. These people all seem to have lots of light and people who stand still while the photographer says, "Watch the birdie" or something like that. Compared to dance, shooting music concerts or other types of stage productions is like rolling off a log. Unfortunately these are often confused and grouped together as all the same.

So, remember the camera can help by not getting in your way or the camera can hinder you. So what specs do we need for the camera? Here, being a dancer may not fill you in with equipment knowledge but being a photographer without dance experience may lead you to think you can use equipment inadequate for dance, cameras which would be fine for something else.

- Able to shoot immediately when you click the button. No shutter lag.

- Optical (direct) viewfinder either through the lens or to the side of the lens. No electronic viewfinders (EVF) which have a time lag between actual events and when they are displayed in the EVF. Not through any screens, not an EVF and not a screen on the back of the camera. These simply take to long to show the image so that when shooting dance the moment is gone when you hit the button. Also, rear-screens as viewfinders (live view) require holding the camera at a distance which is just too unsteady.

- Manual control so that the camera doesn't try to figure out whether it is okay to take the picture first and allows easy manual focusing

- Large aperture lens or lenses (f-stop, the smaller the f-stop the larger the diameter of the aperture) preferable f/2.0 or f/2.8. A typical 3.5 to 5.6 is like living back in 1950 but most camera makers seem to make a ton of these darker (smaller f-stop) cameras, probably because they are less expensive to produce.

- Large ISO, the sensitivity to light. The larger the number the more sensitive. Careful, though. This comes with a penalty, called digital noise. As the ISO is set to ever larger numbers this is like turning up the volume on a radio. As the ISO gets larger so does the digital noise which tends to look like grain in a film camera. The higher it goes the blotchier it gets until the picture becomes unusable. So, software in the camera compensates with digital noise correction which tends to smoosh out image detail. Each year the ISOs get higher and the digital noise correction also gets better so keep checking.

- Audible noise. Reflexes have a mirror (reflector=reflex) to display the image coming from the lens into a viewfinder. To take the picture the mirror has to be moved very quickly out of the way, then release the shutter and drop the mirror back into position. This is an audibly noisy process and will restrict where and how you can take pictures.

- Lens or lenses with a range from wide angle to moderate telephoto such as a long zoom. You want a range which will let you get in physically close for perspective. Normally the long teles should be avoided because they don't allow you to get back far enough to encompass the whole dancer or the whole dance movement. In large aperture versions they are also very expensive.

This tends to mean a reflex (TLR, SLR, DSLR) or rangefinder/viewfinder camera.

Continuous Drive

While you are at it, never get sucked into the continuous drive method (what we used to call motor drive). I know it is kind of a testosterone thing (for both male and female shooters). The reason for using continuous drive (usually three or so shots in rapid succession at each shutter click) is because the photographer wants to have a lot of frames in order to ensure enough pictures. What is not realized is that the frames are at all the wrong moments and that the number of frames almost dictates poor choices.

1 - When the shooter uses continuous drive (motor drive) it is because the shooter doesn't know what to shoot or when to shoot. He or she lets the camera decide. The camera neither hears music, nor sees dance, nor knows the subject. It just has a clock mechanism which clicks to its own timer, regardless of what is happening in front of the lens. Getting "the moment" is absolutely crucial in dance which requires split/split second timing combined with attention (try doing this on a heavy meal -SloooooowToShoot- or a tiny bit of wine -GoesByAndCan'tCatchIt- and see what I mean).

2 - Only shooting single shots, exactly when you press the shutter, will give you the right moments. And not just in dance, in anything. It is still up to the photographer's judgement. The judgement is always working with whatever knowledge the photographer has (or doesn't have). You can tell when a shooter doesn't have specific subject knowledge. They fall back on graphics rules of composition and "angles" and lens to impress and so forth and general people shots which may look nice but could belong to any environment. These tools and devices need to be determined not by their mechanical usage and rules of composition but in the moment by the subject.

3 - Continuous drive (I call it "spray and pray") makes the selections worse in two ways:

a) because the camera's internal timing device clicks the shutter at a rate independent of and complete unrelated to events happening in front of its lens, any good shots are pure accident which just happen to coincide with a good moment in the dance. Most shots don't coincide. Those moments are very, very short which means the shots are almost always just off of the peak moments, either a tad early or a tad late but almost never right on

b) because the photographer uses this as a substitute for knowing what and when to shoot it means the photographer still doesn't know enough to properly pick the right shots from what is now a huge number of exposed frames. Even when the frames are shot well, a large number of frames can be mentally numbing to look through. And here we have a not-so-knowledgeable photog trying to pick good dance frames. That is why again and again when I look at the newspaper shooter's picks they are just not there. Always I think that surely there just must be another shot which really has the moment, not the one that gets published (and after talking to enough dancers I realize I am not alone in this observation).Panic Shooting

This is first cousin to what I call panic shooting or catch-up shooting. By that I mean rapid shooting because you think things are happening so fast that you just need to shoot rapidly. Maybe you saw something go by in the viewfinder and you didn't catch it so now you are hitting the shutter button as fast as you can on everything you see just to get the pictures. Stop! NOW! Slow down and breathe, think and most importantly listen and look. Listen for the count in the music and look to see what is happening in the dance. Then step back in to the count and shoot only as the music tells you.

This is much like dancing and missing a step. Beginners will try to rapidly step, to make sure they get all the steps they missed as they try to catch up. It doesn't work and looks terrible or at least awkward. The only thing to do is focus your attention on listening to the count and then step back into the dance on the count. The missed steps are gone. Just gone. Period. You step back into the dance where the dance is now. Not unlike life itself. If you miss something in life you can't go back. You go on from here. Likewise in shooting. The best way to be sure of getting a full set of good pictures which represents the dance and the dancers is to take your time focusing your attention more carefully and pick your shots only "when you see the whites of their eyes" as they used to say in the old frontier western movies. In other words when you are certain in your timing.

Eyes on the Ball and on ...

I've heard videographers and photographers talk as though dance were merely another type of motion, like sports. I differ, not only about dance but about sports. Some years ago I remember being very excited about football film shot by NFL Films, which not only specialized in football film but which employed as shooters pro and college players, former and current. These were people who really brought their personal knowlege of their own sport to the camera. They use film, even now, not video. It was exciting to me to view the footage.

Here is an excerpt from an article about NFL films - emphases added by me, showing their subject knowledge, before they shot any footage.

Lights, Camera, Action!

by Rudy J. Klancnik (2003 article in American Way magazine)

For more than 40 years, NFL Films has been recording everything from bone-crushing hits to bleep-worthy huddles. Yet each season they still have a few new tricks in their playbook.

They intensely study (game) film and read everything from scouting reports to the local sports pages.

They learn the details of the offense's game plan.

They understand exactly how the defensive coordinator thinks.

Basically, to survive in this game, they must immerse themselves in every facet of what goes on between the yard markers in the National Football League.

But when the ball flies off the tee and the first player dives into the human wedge that protects the kick returner, these guys aren't on the field of play.

It only feels that way. ...Read the whole article from American Way magazine at:

http://www.americanwaymag.com/nfl-films-local-sports-pages-defensive-coordinator-player (2003)

Article quote From in VideoMaker:

Generally, NFL Films only uses three cameras on a regular season game, which Sabol describes as the tree, the mole and the weasel. "A tree is the top camera," he explains. "He's on a tripod rooted into a position on the 50 yard line in the press box and he doesn't move. A mole is a handheld, mobile, ground cameraman, with a 12 to 240mm lens and he moves all around the field and gives you the eyeball-to-eyeball perspective. A weasel is the cameraman who pops up in unexpected places, to get you the telling storytelling shot - the bench, the crowd, all the details."Read the whole article from VideoMaker by Edward B. Driscoll, Jr. (issue: January 2004) at:

http://www.videomaker.com/article/8664

More about NFL Films at:

http://www.NFLfilms.com - Their website

http://digitalcontentproducer.com/mag/video_whole_yards (1 feb 1998)

When I note my excitement at the NFL footage, I need to point out that I am not a sports fan and I look at most sports footage as ho-hum. But, this footage was different and it really caught me. The real lesson here, I decided, is that knowledge of the subject (players and game) makes a genuine difference in the feel of the photograph or the video, for anyone, even when you don't know enough to know exactly why.

Speaking of Athletes

Here are two paragraphs from the include file I have for UMKC dance picture pages. This (and more) appears at the bottom of each of these pages.

I would also call dancers athletes but I hate to, not because they are not athletes but because such statements tend to sound more like an excuse for dance to be tolerated as legit. I think the comparison of dancers and athletes should be more like a multiple of the famous Ginger and Fred comparison which states that she does all the stuff Fred does, but in high heels and backward too.

Dancers don't just move a ball to a goal (so to speak) but they have to do it in character, smiling, with grace and technique specific to the art form, never letting down and never stopping, on beat, keeping count, and repeating exactly the same moves to the same music again and again (you should see some of my comparison videos of separate runs), no mistakes. No cut on traditionally-defined athletes (football, baseball, etc.) and not that there is not tremendous grace in the result, but they get to grunt, groan and grimace with bodies twisted and turned any which way just as long as the ball gets to the goal.

I should also add that the dancers I know are often in various rehearsals for 40 or more hours a week. That is intense muscle work and cardiac work. Those delicate, svelte, lithe bodies on closer examination are tough, flexible, hardened muscles which can endure for hours at a time and yet move as fast and suddenly as any martials arts fighter. Just try standing in toe shoes. For that matter you might think of a dancer's feet in much the same way as a fighter's hands. They bear the brunt of the work. That "pretty little thing" in the tu-tu is probably one of the toughest athletes you will meet.

What You Know

Those of us who started photography early in life and dance later in life are not going to be taking over for Barishnikov, but each dance lesson does leverage our long-term photo knowledge enormously. Those of you who did start dance early in life bring enormous knowledge to the mechanics of the camera. "Subject Knowledge" is the most important camera skill. When you go hunting for the pictures, you already know where they are. You just have a few mechanical details to iron out and get used to.

Good hunting, all.